The relentless churn of fast fashion makes little sense—environmentally, ethically, and often economically in the long run. So why is it so hard to stop?

Sincerely,

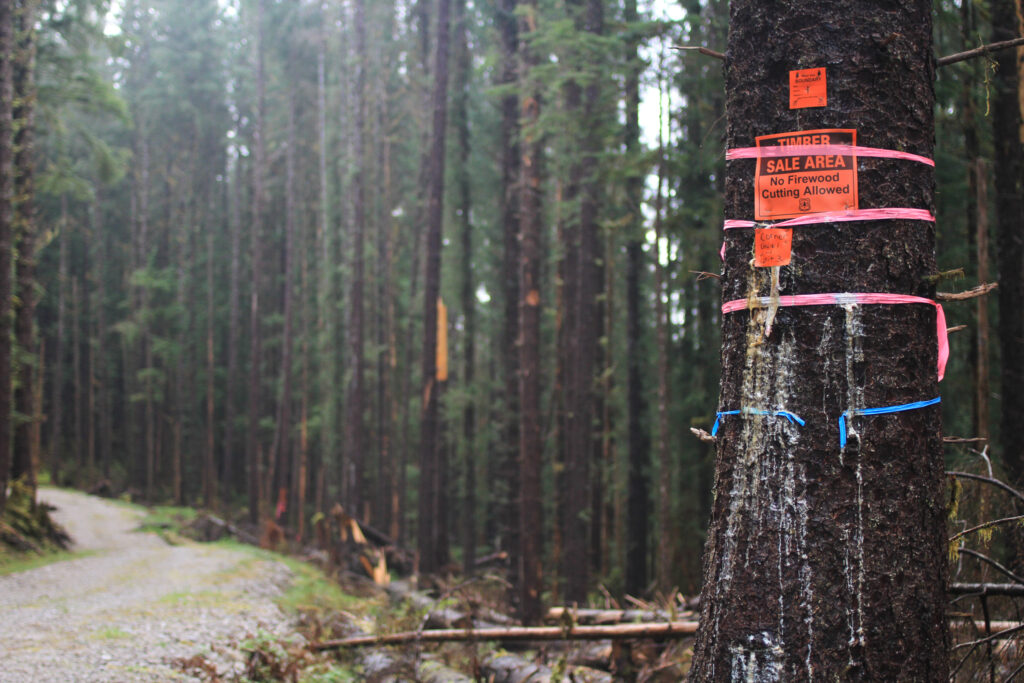

On Prince of Wales Island, southeastern Alaska, Josh Kohn examined harvested logs, highlighting a crucial age distinction: ancient red cedar, likely over 200 years old, versus younger Sitka spruce and western hemlock, aged 35-65 years. Kohn found the younger spruce desirable for its quality and efficient processing. This age difference is presented as a key factor that could reshape the future of both the timber industry and the region’s vast forests, with the ancient cedars bearing the historical memory of Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian peoples.

Having observed environmental conservation efforts across the contiguous United States over the last couple of decades, one might reasonably presume the cessation of old-growth forest harvesting on public lands. Yet, mirroring all other sawmills in Southeast Alaska, Good Faith Lumber—a modest, family-run operation nestled on a remote dirt-road spur—sustains its viability by processing venerable timber from the 16.7-million-acre Tongass National Forest. Remarkably, the Tongass remains the sole national forest in the country sanctioned for industrial clearcutting of primary, ancient stands.

The appeal of old-growth trees lies in their premium, unblemished ‘clear’ grain—highly coveted for architectural interiors; their timber is also greatly esteemed for crafting musical instruments and intricate carvings. This privileged access to ancient timber is paramount for the continued operation of mills in this exceedingly remote region, dominated by the Alexander Archipelago—a sprawling maritime labyrinth of over a thousand islands that fragments from the Alaskan mainland along the Inside Passage. Here, the necessity of extensive maritime transport for logs and milled lumber via barge significantly inflates operational expenditures, far exceeding those encountered in the Lower 48.

The financial solvency of the Tongass timber model proves increasingly elusive. A confluence of market pressures, historical over-harvesting, protracted environmental litigation, and evolving policy directives have conspired to render its traditional sustainability virtually untenable. Consequently, beginning in 2010, U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack and top U.S. Forest Service officials advocated for what appeared to be a pragmatic strategy: to reorient the timber industry towards the selective harvesting of younger, regenerating trees—akin to those piled at Good Faith’s lot and thriving across more than 450,000 previously clearcut acres.

In theory, this pivot would simultaneously safeguard local employment, mitigate legal challenges, and concurrently bolster the region’s vital tourism and fishing sectors. Crucially, it aimed to protect the dwindling vestiges of one of the world’s few massive and still largely intact old-growth temperate rainforests, preserving its enigmatic understory chambers, colossal trunks, and intricate, multi-tiered canopies.

Under a sheltering structure, Josh Kohn and wood-products engineer Catherine Mater convened with mill owners Greg Boyd and Hans Kohn, Josh’s father, to discuss the economic future of Good Faith Lumber. Since acquiring the mill in 2012, Boyd has been a rare proponent of experimenting with younger timber, even purchasing a portion of the Forest Service’s inaugural young-growth sale last year. The mill aims to collaborate with Mater on an economic assessment of harvesting these smaller trees and their potential products.

Boyd articulated his reservations: while he seeks to understand his options, “the jury is completely out on young growth,” noting that processing smaller trees efficiently would necessitate significant equipment upgrades for both the mill and loggers. Nonetheless, Boyd emphasized the need for foresight, pondering whether they should be “reactive when the time comes” or “proactive now and start easing into it,” thereby gaining a market advantage and invaluable experience before the absence of choice dictates their actions.

However, this proposed transition—including the timber sale and Mater’s study—has been beset by complications, mirroring the broader struggles of the Forest Service’s promised old-growth phase-out. Lingering uncertainties regarding young growth’s maturity and market viability, coupled with Forest Service budgetary constraints, entrenched political infighting, and systemic inertia, have profoundly hampered the initiative. Despite six years passing since what appeared to be a path to détente in Alaska’s contentious logging conflicts, the Tongass National Forest has only recently formalized a plan to largely transition away from old-growth logging. Yet, even this long-awaited strategy permits a further 16 years of substantial old-growth clearcutting, and its ultimate enforcement remains precarious, particularly under a potential Donald Trump presidency.

The critical question then looms: how much of the Tongass’s irreplaceable, truly ancient timber will be felled in the interim? As forest ecologist Brian Buma of the University of Alaska, Southeast, soberly asserts, “That is one thing that’s irreplaceable. One thing you just can’t manipulate into existence is big trees.”

On rare clear days, Prince of Wales Island and its neighboring landmasses appear suspended, a terrestrial mirage in the sky, with only a fleeting boat, sea lion, or ribbon of kelp betraying the ocean below. Scars of clearcuts stripe the mountainsides—raw brown where recent, uniformly green with nascent regrowth. Between these, the pristine ancient forest retains a wild, ragged beauty, its silvered deadfall and lichen-draped boughs a testament to age.

The ocean’s lifeblood, salmon, seasonally pulses inland, coursing through a vast network of streams. During my visit, the salmon migration was waning, leaving only a few fish navigating the tannin-stained waters and pale, scattered remains along the banks. The distinct, earthy aroma of the creeks preceded their sight, even from inside a vehicle, prompting passengers to scan for wildlife at the water’s edge.

Bears, eagles, and other fauna are vital vectors, dispersing salmon nutrients across the forest floor, first as carcasses, then as scat. In this intricate cycle, Tongass salmon metamorphose into trees; their nutrient-rich bounty cascades upwards through the soil and into the canopy, nourishing Sitka spruce, cedar, and hemlock, which, in turn, sustain species like Queen Charlotte goshawks, marbled murrelets, and northern flying squirrels.

Yet, over the last century, this oceanic wealth has been siphoned out of the forest, following a parallel network of roads, manifesting as harvested logs that fueled the development of communities like Craig and Thorne Bay. This extraction wasn’t solely driven by timber quality—despite the coveted characteristics of old-growth, such ancient trees often possess defects like rot, and their remote locations presented significant access challenges. Indeed, when Bernard Fernow, the “father of North American forestry,” surveyed these very woods during an 1899 expedition, he famously concluded that the formidable terrain and vast distance from markets meant that “this reserve will, for an indefinite time, be left untouched except for local [use].”

The genesis of extensive timber operations in the Tongass was a protracted endeavor, eventually catalyzed by a U.S. government keen on fostering settlement for national security, coupled with a significant surge in Japanese demand for post-war reconstruction. The pivotal transformation commenced in the 1950s, solidified by two half-century contracts that guaranteed two colossal pulp mills a consistent, inexpensive supply of vast quantities of timber from the Tongass National Forest. These industrial operations proceeded to masticate ancient trees, transforming them into products ranging from rayon to diapers.

The legislative landscape further accelerated this exploitation: the 1970s saw a new law incentivize widespread forest liquidation on hundreds of thousands of newly privatized tribal lands. A decade later, the 1980s brought forth another statute that established astronomical timber subsidies and unprecedented harvest levels on the Tongass, ostensibly as a trade-off for conservation initiatives elsewhere.

This period was one of immense bounty, as recalled by former logger Robert Rowland over a pint. He recounted his tenure on Long Island, just south of Prince of Wales, a location where some of the Tongass’s most gargantuan trees once stood. Rowland’s vivid description evoked an almost primeval grandeur: “It was like logging the redwoods. Like going into Jurassic Park. I wouldn’t have been surprised if a dinosaur came running out.”

The bonanza’s largesse, however, proved ephemeral. By the 1990s, a convergence of factors—stringent pollution enforcement, escalating environmental opposition, and global pulp market volatility—led to the demise of both monumental pulp mills. Concurrently, significant legislative and policy reforms instigated new protections, such as designated old-growth sanctuaries and no-cut buffers along waterways, which curtailed the most egregious logging practices. Some of these had so ravaged certain watersheds with landslides and fish-choking sedimentation that one stream was infamously nicknamed FUBAR (an acronym for “f#@%ed up beyond all recognition”).

Nonetheless, a new wave of loggers and mill operators migrated to the region, some seeking sanctuary from the old-growth access they’d lost in the Northwest’s “spotted owl wars” of the 1980s and 90s. Viking Lumber, now the largest remaining mill in Southeast Alaska, repurposed a bankrupt sawmill in Klawock, Prince of Wales Island, and commenced acquiring timber sales in the permissible sections of the forest. Yet, the newcomers soon confronted the undeniable reality that Alaska was also undergoing a profound transformation. For instance, President Clinton’s 2001 Roadless Rule designated nearly 60 million acres of undeveloped national forest nationwide as off-limits to road building, including a substantial 9.5 million acres within the Tongass.

Tongass National Forest harvests plummeted from an annual average of 220 million board feet during the pulp mills’ final throes in the 1990s—enough lumber to construct approximately 13,400 average American single-family homes—to a mere 33 million board feet annually over the past decade. Between 1998 and 2012, the region endured the dismantling of nearly 1,000 timber jobs, stabilizing around 250, while the number of active mills halved to just 10, crippling several communities. Conversely, other private-sector employment, notably in tourism and commercial fishing, which now collectively account for one in five positions, burgeoned by 1,400 new jobs.

Here, the saga of the Tongass bifurcates into two dichotomous narratives. The industry’s perspective contends that old-growth timber, despite its abundance, has been unduly sequestered by environmental activists and mismanaged by an ineffective federal government. Indeed, a mere 12 percent of the prime ancient forest—that which grows more quickly and yields higher quality timber—has been harvested across public, state, and private lands.

The counter-narrative, championed by environmentalists, underscores the Tongass trees’ stark variability in quality and the grim reality that the majority of the most superior and largest specimens have already been felled, decimating the region’s crucial wildlife habitat. When Josh Kohn first arrived on Prince of Wales from the Olympic Peninsula, he was taken aback by the comparatively diminished stature of most local old growth. “I’ve seen limbs that size in the Washington rainforest,” he remarked, highlighting the contrast. Today, the landscape boasts dramatically fewer trees exceeding three feet in diameter—not to mention the exceedingly rare Sitka spruce behemoths surpassing 10 feet across—than it once did. What remains of the richest forests is severely fragmented, with extensive, unbroken stretches of big-tree old growth diminished by 66 percent region-wide, per a 2013 analysis. On the highly productive northern Prince of Wales Island, the situation is even more dire, with a staggering 94 percent having vanished.

The repercussions of this degradation reverberate globally. Deforestation currently contributes approximately 12 percent of worldwide anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, and the Tongass’s mature forests are significantly superior carbon sinks compared to their younger counterparts. By a widely cited estimate, its ancient trees, soils, and bogs collectively sequester a staggering eight percent of all carbon stored in U.S. forests. As logging devoured these stands during the industry’s peak decades, the national forest’s net emissions—stemming from slash, roots, soil, and ultimately the wood products themselves, which are far less effective at sequestering carbon than living trees—surged fivefold.

For these and myriad other reasons, environmental groups have resolutely championed the remaining public-land old growth. Consequently, timber sales are mired for years, and management plans languish in legal purgatory. Even previous attempts at compromise have foundered and fractured, often exacerbating existing divides even as nascent collaborations emerged. With some of the same individuals locked in decades-long antagonism, the disputes often descend into rancorously personal battles, even among those sharing similar broader objectives. As one public-lands expert remarked, “I don’t think I’ve ever covered a more vitriolic dispute.”

Kirk Dahlstrom, co-owner of the Viking mill, is blunt about the ongoing impasse: “Our company has spent close to $1 million on attorneys fighting environmental lawsuits. I hate it.” When pressed on his persistence, he retorted, “We’re Swedes, we’re too stupid to give up.” Then, with a more subdued tone, he added, “I’m fighting for the next generation.”

A long way up a bone-jarringly rutted logging road, Catherine Mater and Michael Kampnich—a commercial fisherman and former logger now with The Nature Conservancy—emerged from Mater’s rented SUV into a sun-dappled afternoon. This was Dargon Point, the nine-acre young-growth tract Good Faith had secured the rights to harvest. Roughly 70 years old, these trees possessed a surprising stature, appearing taller and thicker than anticipated. Mater indicated a spruce with whorls of narrow branches, which would manifest as knots in milled boards.

“These limbs are kind of more tightly spaced than I like to see, but you’ll see a lot of wood like this going into ceiling and paneling product, and it’s gorgeous,” she observed. While knottier wood commands a lesser premium than the old-growth “clear,” younger trees inherently exhibit fewer defects like rot and lack the deep fissures that ancient trees can develop over time in their heartwood due to environmental stressors like wind flex or frost penetration. Consequently, over 50 percent of old-growth trees from some timber sales might be rendered unusable for these reasons, meaning entire stands are decimated for the mere fraction of timber that yields profit for loggers.

Kampnich, however, introduced a caveat: “See all the dead stobs sticking out?” he inquired, pointing at gnarled branch remnants protruding from another trunk. These, he explained, can become “loose knots,” meaning that when thinner boards cut from the outer edges are kiln-dried, the knots can dislodge, leaving the lumber marred with voids. This particular challenge underscores why Mater and Good Faith are seeking support to rigorously test which products these younger trees are most suitable for—be it thinner boards and paneling, or more robust beams and cabin logs.

Despite how paramount this kind of information is for orchestrating the industry’s pivot to young growth, Mater’s efforts have been fraught with friction. “These are projects I enjoy doing because they’re tough,” she told me. “If they move forward, they’re a point of inflection that allows a sea change.”

Mater embarked on studying the Tongass’s young-growth conundrum in 2011, intensifying her work after a 2013 USDA directive mandating a 10- to 15-year deadline for a transition out of old-growth reliance. The Geos Institute, a climate-adaptation nonprofit, and the Natural Resources Defense Council had commissioned her to ascertain the feasibility and pace of this transition. She achieved this by assessing the potential yield of young growth from previously disturbed areas along existing roads. Mater’s GIS and field surveys of disparate stands ultimately suggested that the new trees were not only larger than expected but could furnish sufficient volume to largely wean the local industry from old growth by as early as 2020—contingent upon the Good Faith study and analogous research yielding favorable outcomes and actually progressing. “Ultimately,” Mater asserted, “if our volume projections prove even half accurate, it will fundamentally re-engineer this industry.”

Geos, NRDC, and a coalition of other green groups had hoped the Forest Service would interpret the survey’s findings as an impetus to accelerate the abdication of old-growth reliance, a prospect that garnered significant external endorsement, including a unanimous 2015 letter from seven scientific societies. “I am sensitive to the fact that these are rural communities where every job matters,” said Dominick DellaSala, president of Geos. “That’s why we said, ‘If you go this way, you get a wall of wood. If you go this way, you get a wall of litigation.’ We were trying to help.”

Ultimately, the Forest Service opted to disregard Mater’s data, citing, among other concerns, its divergence from the agency’s own laboratory findings and the imprudence of her proposed five-year timeline for industry adaptation. The agency’s underlying rationale was likely imbued with political considerations. Mater’s affiliation with staunch environmental advocacy organizations compromised the perceived objectivity of her surveys, particularly as key industry representatives categorized them as excessively sanguine.

Meanwhile, Dahlstrom and his son have publicly articulated dire warnings that Viking Lumber—a critical employer of 38 individuals and dozens of contractors in a region plagued by high unemployment—is already perilously close to shuttering. They contend that the Forest Service’s current allocation provides the mill with scarcely sufficient old-growth timber to sustain operations. “‘When we are in a second-growth supply situation,’ Dahlstrom declared unequivocally, ‘Viking will cease to exist.’”

While Southeast Alaska’s timber industry is ostensibly modest in scale, it wields considerable influence over state authorities and Alaska’s congressional delegation. Both have advocated strenuously for a prolonged 20- to 30-year transition period for young-growth harvesting, coupled with sustained, higher old-growth quotas. This stance has, in turn, exerted substantial pressure on the Forest Service. Alaska’s Republican Senator Lisa Murkowski, notably, chairs a formidable committee with direct fiscal oversight of the agency’s national budget.

However, Vilsack’s 2013 order endeavored to forge a compromise: it mandated the Forest Service convene a collaborative group comprising representatives from indigenous tribes, the state, industry, environmental organizations, and other stakeholders. Numerous consensus recommendations from that advisory committee have since been incorporated into a new plan recently formalized this month. This new framework stipulates a 16-year timeline that initially maintains old-growth harvest levels broadly equivalent to current totals for the first decade, augmented by a modest young-growth component. The plan then calls for a gradual transition to diminished old-growth extraction and escalated young-growth harvesting, until the annual allocation stabilizes at 41 million board feet of young growth (with a projected increase) and a mere 5 million board feet of old growth. This projected output would nonetheless accommodate many of the smaller mills and artisans—Good Faith, for example, currently processes approximately 800,000 board feet annually, despite possessing a capacity for 5.5 million.

The plan also designates important watersheds and ecological areas as off-limits to old-growth logging, and for the first time formally enshrines the long-contested Roadless Rule protections. Yet, it omitted crucial committee recommendations that environmentalists deemed vital for ensuring the transition’s enforceability, particularly a five-year deadline for planning the substantial old-growth timber sales intended to sustain the industry until younger trees mature. “I think without that, we’re apprehensive that any future administration can perpetually harvest old growth, and policy will be subject to the capricious dictates of the mills,” stated committee member Andrew Thoms of the Sitka Conservation Society.

Furthermore, the plan incorporated a contentious provision that permits limited thinning and even clearcutting of young stands within previously established protected areas, including designated old-growth reserves. This provision is designed to guarantee that sufficient young-growth timber is accessible to support the industry. However, despite its included habitat restoration component, this has elicited vehement opposition from virtually the entirety of Alaska’s environmental community, alongside sharp criticisms from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

The plan also designates important watersheds and ecological areas as off-limits to old-growth logging, and for the first time formally enshrines the long-contested Roadless Rule protections. Yet, it omitted crucial committee recommendations that environmentalists deemed vital for ensuring the transition’s enforceability, particularly a five-year deadline for planning the substantial old-growth timber sales intended to sustain the industry until younger trees mature. “I think without that, we’re apprehensive that any future administration can perpetually harvest old growth, and policy will be subject to the capricious dictates of the mills,” stated committee member Andrew Thoms of the Sitka Conservation Society.

Furthermore, the plan incorporated a contentious provision that permits limited thinning and even clearcutting of young stands within previously established protected areas, including designated old-growth reserves. This provision is designed to guarantee that sufficient young-growth timber is accessible to support the industry. However, despite its included habitat restoration component, this has elicited vehement opposition from virtually the entirety of Alaska’s environmental community, alongside sharp criticisms from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Loggers and their allies remain unmollified, amidst the lingering ambiguities regarding the future readiness and volume of young-growth timber. The Forest Service and Alaska initiated an extensive three-year survey this summer to ascertain these specifics, yet, even prior to its completion, the state’s U.S. congressional delegation has already vowed to impede the transition plan under the next administration. “We were not given the choice to decide if the Tongass should transition to Young Growth,” Eric Nichols, a committee member and partner in a large log-exporting business called Alcan Forest Products, fulminated by email in October: “This was a unilateral political decision orchestrated in Washington D.C., entirely devoid of genuine public involvement.”

To experience a vestige of Prince of Wales’ past magnificence, Bob Claus—a veteran of both state law enforcement and conservation leadership, having served as a state trooper and interim executive director of the Southeast Alaska Conservation Council—guided me to the protected Honker Divide. Pushing through a dense verdant curtain of roadside conifers, we stepped into a hushed, emerald sanctuary, ethereally luminous even beneath the somber, clouded sky. Above, the expansive, plate-sized foliage of formidable devil’s club thickets (Oplopanax horridus)—whose barbed spines effortlessly pierce rain gear and inflict painful, weeping lesions—diffused a soft, golden glow. Beneath, berry bushes and various shrubs arched gracefully over a velvety carpet of moss that radiated an almost otherworldly, incandescent green. Beyond this intertwined undergrowth, colossal Sitka spruces ascended, their impressive girth and sky-piercing crowns hinting at immense age.

“This first step [into old-growth] is the coolest thing ever,” Claus exclaimed. He characterized the environment as a “Tolkien thing,” a “magic forest,” noting, “In wintertime it looks just like this. There’s tons of stuff for all of the deer and critters to eat.” The forest’s dense, interlocking canopy, punctuated by natural openings created by fallen trees and other disturbances, permits sufficient light penetration to foster a thriving, nutrient-rich understory while simultaneously buffering against heavy snowfall. This unique synergy renders it a critical refuge and sustenance ground. These invaluable benefits are notably absent in younger stands.

This ecological disparity is precisely why conservationists express profound apprehension over a perpetually extending transition timeline: it portends the piecemeal attrition of vital, wildlife-sustaining old-growth habitat within the designated harvest zones—areas already bearing the scars of extensive logging.

Indeed, a monumental old-growth timber sale called Big Thorne—which the Forest Service envisioned as the foundational cornerstone propelling industry toward its young-growth future—is proceeding apace, notwithstanding profound concerns regarding the local Alexander Archipelago wolf (Canis lupus ligoni) population.

In 2013, Dave Person, the outgoing Alaska Department of Fish and Game wolf expert, intervened to halt the sale encompassing over 6,000 acres, submitting a compelling brief that warned the harvest and its concomitant road construction could irrevocably undermine Prince of Wales’ fragile equilibrium among humans, wolves, and Sitka blacktailed deer (Odocoileus hemionus sitkensis)—an essential subsistence resource for rural communities. Wolf populations were already in a precipitous decline, exacerbated by logging roads that granted hunters and poachers unfettered access to their habitats. Concurrently, deer faced exacerbated vulnerability with persistent cover loss. Person cautioned that if the deer population suffered a demographic collapse—a scenario witnessed in other heavily logged sections of the Tongass during severe winter conditions—it would intensify pressure on wolf populations as residents contended for their share of game.

Ultimately, the Forest Service, in collaboration with the state, opted to implement restricted wolf hunting as a mitigation measure, foregoing substantial modifications to the timber sale. Viking, having secured the lucrative contract, commenced logging operations in 2015, amidst persistent legal challenges. This decision, Person lamented this October, has profoundly diminished any prospect of wolf population recovery. “When I started work there beginning in the 1990s, our estimate was 300 to 350.” This year, the estimate plummeted to a mere 69 to 167. “It’s a poignant Greek tragedy in my mind—the whole narrative is predetermined, everybody plays their role, and the cycle remains unbroken.”

Meanwhile, the forest’s rare, slow-growing, venerable red and yellow cedar (Cupressus nootkatensis) trees face the imminent threat of extirpation from unprotected parcels under a protracted timeline for old-growth logging, warns Juneau-based naturalist Richard Carstensen, who has conducted extensive ecological surveys of the region. This dire prospect stems from the fact that their exceedingly coveted timber is among the few remaining factors rendering timber sales in the region economically viable. Carstensen passionately argued, “What intrinsic value is there in these being the last truly ancient cedar forests in the world? Why not simply safeguard them precisely for that reason?” He further posited, “If instead of merely quantifying loss by annual wood volume, we were to assess the decades required to cultivate the felled trees, we might uncover that current logging rates on public and private land now mirror or even surpass the ‘decades of ecological hemorrhage’ witnessed in the 1960s and ‘70s. I believe our heads are in the sand.”

Yet, this current unsustainable depletion may signify that the large-scale old-growth timber industry is already facing inexorable decline, driven by fundamental economic realities. The industry has historically necessitated substantial public subsidies to remain economically viable in this remote region. A 2016 Government Accountability Office report revealed that while the Tongass allocated an average of $12.5 million annually to its timber program from 2005 to 2014, it generated a meager $1.1 million in average annual revenue.

Despite persistent federal expenditure and the Forest Service’s increasingly liberalized restrictions on raw log sales to higher-value export markets, the industry has continued to flounder. Conservationists assert that the supply of old trees—sufficiently valuable, densely concentrated, and readily accessible to justify their extraction from these rugged landscapes—is simply rapidly diminishing. This scarcity is compelling loggers to exploit slower-growing and more economically marginal stands in a desperate quest for remaining timber. The Forest Service itself was forced to scramble to piece together disparate fragments of forest across the landscape merely to cobble together the requisite acreage for the Big Thorne sale. Some, including Nichols and Dahlstrom, attribute the industry’s predicament to the Roadless Rule; the Forest Service concurs that it complicates timber sales. Yet, others contend that its repeal would be inconsequential, arguing that the forest swathes it safeguards are roadless precisely because they were inherently unfeasible for development in the first place.

Given the current rate of old-growth extraction, David Albert, director of conservation science for the Alaska chapter of The Nature Conservancy, ominously predicted, “I don’t think we have 15 years.”

Coffman Cove, nestled on the northern reaches of Prince of Wales, presents itself as a well-ordered cluster of structures hugging a pristine, vessel-dotted bay. Progressing past the local school and its nascent wood-fired greenhouse—poised to teach students hydroponic cultivation—and beyond the quirky landmark of plastic flamingos I’d been instructed to spot, I discovered Misty Fitzpatrick’s residence, its rear facade abutting the sea. Inside, the 35-year-old Fitzpatrick, her dark hair gathered in a bun and possessing a forthright demeanor, attended to a colander-full of freshly shucked oysters.

She was raised amidst the ephemeral floating logging camps that once migrated along the island’s shores. Her father felled timber for a pulp mill, meticulously tallying his output on his hard-hat brim with a wax pencil—a record for the generous wages that afforded his children comfort when they weren’t roaming wild in the surrounding forests. Fitzpatrick is eager to replicate that unfettered childhood for her own 5-year-old daughter. “She loves to go out and hunt and fish. You can instill true capability in your children,” she remarked, adding with a wry smile, “You just have to work harder to get ’em socialized.” As if on cue, a tiny, pants-less girl streaked into the house—fresh from pursuing salmon up a creek.

However, Fitzpatrick no longer sustains her daughter through logging wages. Though Coffman Cove originated as a logging camp, its contemporary employment base predominantly lies in tourism, fishing, local governance, construction, and education. In essence, the community has already effected this transition—for better or worse—a pattern mirrored across most Southeast communities, many of which now rely heavily on cruise ship traffic. Fitzpatrick’s oysters, for instance, were destined for a road-paving crew lodged in her five rental cabins. This town of just 180 permanent residents boasts a remarkable 125-plus guest beds, as Fitzpatrick noted. “I cherish this community. My foremost concern is our diminished capacity to attract families. It is increasingly becoming a haven for retirees.”

This demographic shift can jeopardize the viability of rural schools, as state funding rules mandate a minimum of 10 students. Fitzpatrick recalled a robust 30 or 40 students when she was a child in Coffman Cove. Today, notwithstanding its impressive facilities, the school now numbers a mere 13. Meanwhile, Prince of Wales’ unemployment rate persists above 12 percent, doubling the state average.

When I met her, Fitzpatrick and a cohort of other community leaders were mobilizing to tackle some of these issues through the prism of natural resource management. Their objective is to furnish the Forest Service with a curated list of locally significant projects, concurrent with the agency’s efforts to amass data to expedite the on-the-ground transition. She aspires for this initiative to forge a more resilient foundation for the island’s communities, bridging the past timber boom and the nascent tourism boom.

It remains ambiguous whether future young-growth logging will prove more efficacious than current old-growth practices. If local mills merely produce commodity lumber, they will struggle to contend with the colossal, automated mills processing young growth globally. Furthermore, as the majority of local mills lack the requisite machinery, young trees will initially be destined primarily for Asian export markets. This approach will bolster contract employment—for loggers, truckers, dock workers, and ancillary personnel—and concurrently facilitate forest-thinning initiatives aimed at restoring wildlife habitat within the dense, regenerating second growth. However, significantly greater employment could be generated if companies pioneered local processing of younger trees into value-added materials. This remains the foremost aspiration for those endeavoring to harmonize conservation imperatives with timber-sector employment in the region. And for now, at least, it appears tantalizingly out of grasp.

On my final day on Prince of Wales, as I awaited my departure, my thoughts reverted to the diverse individuals I’d encountered in the island’s communal gathering places: commercial fishermen, guides, lodge owners. There was Robert Rowland, a veteran logger who revealed his crane-operator position now accrues him five times the remuneration he earned in the timber. And Stacy Skan, a young islander who, after departing for academic pursuits and repatriating with a master’s in organizational management, confronted a stark dearth of prospects. She and her boyfriend contemplated relocating to the mainland within the ensuing twelvemonth. “It inflicts a poignant sorrow to be compelled to depart,” she had confided to me. “We perceive few viable alternatives.”

The continued presence of a timber industry here is inherently logical: Alaskans require timber, and the forests are vast. Yet, the evolving global economic landscape appears to be compelling these isolated communities and their residents toward alternative economic trajectories. The emerging future, regardless of its form, will bear even less resemblance to the halcyon days of the pulp mill era than the present configuration. The sole certainty, however, is that this future, too, will be indelibly shaped by the Tongass itself—by its historical scars, its resilient grandeur, and above all, by the formidable isolation that has perennially defined its brooding, rain-swept expanses.